We work hand in hand with our clients to develop and evolve products over time

Research, develop and grow with us

80 Trials and Triumphs or Historia Magistra Vitae Est

This April will mark 80 years since the founding of the "Niko" Metalworkers' Productive Cooperative with Limited Liability, the predecessor of today’s Domel. In this article, we will explore the lessons offered by our rich treasury of experience - from both the recent and more distant past—and how they apply to the challenges of the present day.

Few places in Slovenia enjoy the luxury of a centuries-old industrial tradition, which offers the open mind the privilege of learning from the examples of its predecessors. From individual records, we can trace the challenges faced by enterprising predecessors from the late Middle Ages onwards and see how their struggles were, in many ways, remarkably similar to those of today.

In our region, life-written examples can be traced back to the first five ironmasters in the mid-14th century. As we shall see, unlike the founders of today's company, they were incentivized by the ruler of the time, Bishop Albert of Freising, with grants of land for development, free use of forest resources for their needs, and free passage on the roads of that era. However, the following century already brought difficulties due to frequent Turkish raids and their plundering of the land. Furthermore, between 1508 and 1516, a war with the Venetians took place, leading to increased military taxes. The additional burdens of repairing material damage after the great earthquake of 1511, followed by an outbreak of the plague, resulted in the people of Železniki joining the pan-Slovenian peasant revolt in 1515. The uprising was bloodily suppressed, and the inhabitants lost their original privileges, regaining them only six years later, in 1521. As the Emperor also began asserting authority over mineral wealth in the 16th century, disputes between the Freising feudal lord (or his deputy from Škofja Loka) and the people of Železniki became increasingly frequent.

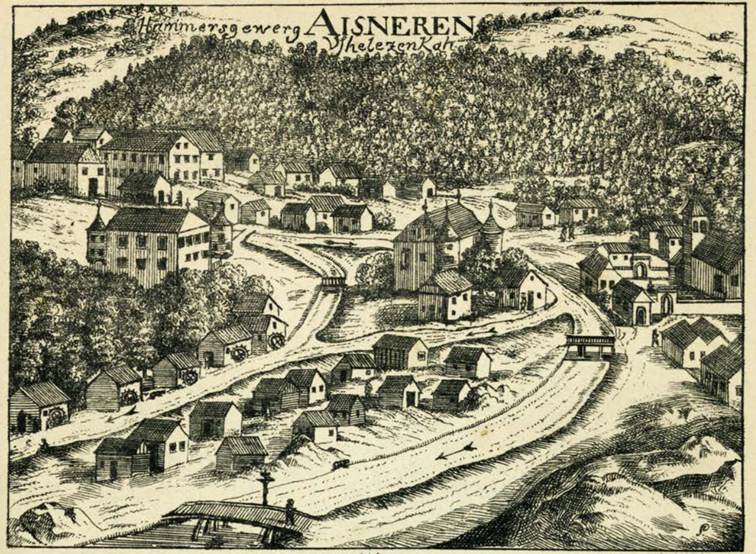

Nevertheless, towards the end of the 17th century, Janez Vajkard Valvasor, in his work Slava vojvodine Kranjske (The Glory of the Duchy of Carniola, 1689), describes how the Železniki mine had flourished since the end of the 14th century and that, at the time of his writing, "Shelezenke" (Železniki) boasted large and beautiful masonry houses. He enthusiastically describes the forging of the "bloom" (iron mass) and notes that a great deal of iron was produced there, which was further fashioned into all kinds of weapons and an especially large quantity of nails.

Source: EHRE des HERZOGTHUMS KRAIN, Johann Weichard Freiherrn von Valvasor, Laibach-Nurnberg, 1689.

Only a century later, the French surgeon and naturalist Balthasar Hacquet described a completely different set of circumstances in his book Oryctographia Carniolica (1781). The mineral resources were depleted, the ore extraction processes were obsolete, and the shareholders of both ironworks—with the exception of one or two—were impoverished and lacked knowledge of the industry. During three visits over a period of twelve years, he observed no progress whatsoever. Consequently, he recommended the merging of shares into a joint venture and the construction of a single high-piercing blast furnace that would operate year-round.

Source: EHRE des HERZOGTHUMS KRAIN, Johann Weichard Freiherrn von Valvasor, Laibach-Nurnberg, 1689.

The conversion of the bloomery furnaces into high-piercing blast furnaces finally took place over half a century later, but it could no longer halt the industry's decline. Hand-forged nails were no longer competitive against the machine-made ones being produced in Jesenice, while in Kropa, smiths merged into a cooperative and pivoted toward new niche markets, such as railway spikes.

The iron industry finally collapsed at the beginning of the 20th century. With no new industry to provide employment for the large class of blacksmiths, the town and its surroundings sank into half a century of poverty. Despite occasional attempts at a revival, the true turning point came after World War II, on April 27, 1946. The story of the 16 determined visionaries and the numerous challenges they faced during the founding of the cooperative and in the years that followed remains relevant to this day. They serve as a precedent and a prime example of best practice: what to do when the business environment is far from encouraging.

Photo: Janez Tolar, april 2025.

Records show that upon its founding, the cooperative received no support from the central republic authorities. Consequently, they faced difficulties with financing and the supply of appropriate raw materials; the initial production program was limited, and there was a severe shortage of skilled labor. They increased their fixed assets through voluntary work, contributing up to 200 hours per year. They rapidly expanded their product portfolio, and during periods when production work was scarce, they renovated workspaces and built other critical infrastructure, such as a water pipeline and their own hydroelectric power plant. Knowledge was gained through cooperation with external partners, including prisoners of war. Aware of the importance of expertise, they conducted internal training and began awarding scholarships very early on to attract highly qualified colleagues. Since widespread poverty had prevailed for decades following the collapse of the iron industry, the primary motivation for the cooperative members was work with human dignity and fair compensation. The main founder and the first president of the cooperative noted that the level of working enthusiasm seen in the first years of the cooperative's existence was never matched before or since.

Source: Iskra in Železniki, on the 35th anniversary of modern metalworking.

Despite the great dedication and mutual support of the employees at the time, records further describe how dark clouds began to gather over the factory after a good decade of successful growth. In accordance with state directives, they were forced to abandon their automotive industry program, even though it had been the foundation for the investment in the new production and administrative building at the current "Otoki" location. The production range began to shrink, while quality and productivity suffered. The transition to the mass production of small electric motors, featuring the first assembly line in the early 1960s, required more effort than anticipated. Investment funds were non-existent, and all this was accompanied by internal disagreements. It was primarily due to the persistent efforts of all employees that the first signs of success began to emerge after four years of crisis. During these years, a reorganization took place, culminating in 1962 with the integration into the ISKRA corporation, followed the next year by the re-establishment of the NIKO craft enterprise, to which the production of office stationery was transferred.

Specialization in the field of mass-produced electric motors brought renewed growth. However, as early as 1966, severe difficulties arose due to the cancellation of orders by a leading foreign customer; consequently, for a year and a half, wages were paid at 80 percent. Prior to this, results had also declined due to rising material costs, high inflation, an increase in accounts receivable, and problems with the supply of components. General illiquidity prevented greater success. In the 1960s, 70s, and 80s, market share was gained through cooperation with domestic and foreign companies. In exchange for electric motors, they received household appliance components, which they then sold on the heavily regulated Yugoslav market of the time. The breakthrough that shaped the company in the long term was achieved through a "cross-selling" deal: while negotiations with a West German customer were initially held for the supply of compressors, the final deal was realized in 1976 with the start of mass production of vacuum motor units.

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, periods of good and bad years alternated. While the product portfolio and number of production sites expanded, the era was primarily characterized by reorganizations driven by state and external pressures. The most significant change—both from the perspective of ownership and for the survival of the company as an independent entity—occurred in the 1990s. To prevent a takeover by a foreign competitor, the employees pooled their ownership stakes. In doing so, they acquired a majority share and, with it, the management of the company. In the early 1990s, the product portfolio was consolidated, which led to a high level of dependence on a single market. From today's perspective, the start of regular production of electronically commutated (EC) motors was also a major milestone. More intensive market diversification began after 2000; however, these ambitious plans were slowed down by the global financial crisis at the end of the first decade of the new millennium. Due to a decline in orders, we spent our Fridays at home for part of 2009.

A period of stable growth resumed after 2012, which came to an end in 2020 with the outbreak of COVID-19. Since then, we have faced a succession of diverse global crises - recurrent waves of the aforementioned pandemic, the wars in Ukraine and Gaza, high energy prices, tariffs, disrupted supply chains, and a general slowdown in economic activity.

A brief overview of history reveals that similar challenges have emerged in every era. Our predecessors overcame them through proactive engagement, investment in new products and their associated technologies, a commitment to knowledge, and, above all, through cooperation. Considering all the obstacles that past and present employees have managed to surmount with perseverance and creativity, such a significant anniversary seems all the more worthy of respect.

More Domel insights:

For more than 65 years, Domel has been a global leader in the development of high-performance vacuum motors. Through engineering excellence, innovation, and reliability, we support leading manufacturers of cleaning equipment worldwide. Domel in brief Domel vacuum motors are recognized for their efficiency, durability, and advanced design: Ultra-low vibration levels and quiet operation Best-in-class aerodynamic efficiency (> 55%) 10–30% lower material usage with equal performance Highly automated production with 100% final inspection These strengths make Domel a trusted long-term partner for demanding cleaning applications. Innovation for Modern Cleaning Needs As wet & dry vacuum applications continue to grow, Domel develops advanced EC (brushless) motor solutions for residential, commercial, and industrial environments—combining high efficiency, long lifetime, and robust design. With solutions covering a voltage range from 18 to 230 V, Domel enables both battery-powered and mains-powered applications, offering maximum flexibility for modern cleaning equipment design. Proven and Future-Ready Solutions Domel’s portfolio combines proven reliability with next-generation innovation: 467 – A global standard for durability in wet & dry applications NEW! 457 and 759 – New-generation solutions designed for improved efficiency, sustainability, and future regulations New vacuum motor 457 New vacuum motor 759 Ready for the Future of Cleaning By combining decades of experience with continuous innovation, Domel continues to shape the future of vacuum motor technology and high-performance suction solutions.

Read article

In recent days, Dubai has been the center of global healthcare innovation.

Read article

In 2026, Domel proudly marks 80 years of innovation and tradition, which we will celebrate throughout the first half of the year with a rich program of events, open house days, and anniversary exhibitions.

Read article

Thank you for being part of our journey!

Read article